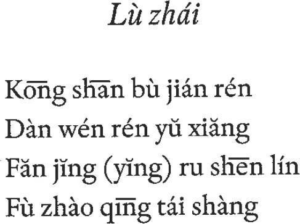

Wang Wei (c. 700—761), a Buddhist master poet from the Tang Dynasty, composed the above poem amidst a series of nineteen others that combined to form a long-scroll quatrain, the first of its form. Wang Wei’s quatrain focused on the various sights about the Wang River, with each poem serving to illustrate a variety of landscape-based elements inspired by these locations. The above poem, which is sometimes transliterated as “Lù Zhái,” has been translated numerous times historically, as Eliot Weinberger details in Nineteen Ways of Looking at Wang Wei (2016), a collation of translations that span the last nine-hundred years. Yet I maintain that these translations, as well as the commentary provided by Weinberger, neglect the key formative elements that encapsulate the beauty of Wang Wei’s original Mandarin poem.

Weinberger provides the following transliteration, as well as a character-by-character “crib,” a usually unintelligible construct depicting the equivalencies of one singular character. Cribs are used as a tool for translators as an intermediate step between transliteration (from original Chinese characters, as above, to the modern Romanic alphabet, as with the pinyin below) before translating into the target language (i.e., English).

Part of the difficulty is that, while the language itself hasn’t changed – that is to say, the original Mandarin characters have not evolved since the Tang Dynasty – the pronunciation in modern Chinese has changed over time. Weinberger writes:

Chinese has the least number of sounds of any major language. In modern Chinese, a monosyllable is pronounced in one of four tones, but any given sound in any given tone has scores of possible meanings. Thus a Chinese monosyllabic word (and often the written character) is comprehensible only in the context of the phrase: a linguistic basis, perhaps, for Chinese philosophy, which was always based on relation rather than substance. (8)

This, understandably, presents a dilemma: with nearly every character almost having more than one meaning, and such a short poem providing minimal context, how can translations be faithful? The short answer to this question is that they can only try to be. However, certain intuition gives precedence to specific definitions over others.

After studying previous iterations of Wang Wei translation efforts, as well as doing additional research, I embarked on the adventure of crafting my own translation. However, I needed to review some of the historical scholarship in order to fully comprehend the historical picture and gain access to both past insights and points of debate. While Weinberger’s piece delves into nineteen interpretations, here I will focus only on a few.

[1]

The Form of the Deer

So lone seem the hills; there is no one in sight there.

But whence is the echo of voices I hear?

The rays of the sunset pierce slanting the forest,

And in their reflection green mosses appear.

– W.J.B. Fletcher, 1919

(Fletcher, Gems of Chinese Verse)

[2]

La Forêt

Dans la montagne tout est solitaire,

On entend de bien loin l’écho des voix humaines

Le soleil qui pénètre au fond de la forêt

Reflète son éclat sur la mousse verte.

[The Forest.

On the mountain everything is solitary,

One hears from far off the echo of human voices.

The sun that penetrates to the depths of the forest

Reflects its ray on the green moss.]

– G. Margouliès, 1948

(Margouliès, Anthologie raisonnée de la littérature Chinoise)

[3]

On the empty mountains no one can be seen,

But human voices are heard to resound.

The reflected sunlight pierces the deep forest

And falls again upon the mossy ground.

– James J. Y. Liu, 1962

(Liu, The Art of Chinese Poetry)

[4]

Deer Fence

Empty hills, no one in sight,

only the sound of someone

talking; late sunlight enters the

deep wood, shining over the green

moss again.

– Burton Watson, 1971

(Watson, Chinese Lyricism)

[5]

En La Ermita del Parque de los Venados

No se ve gente en este monte.

Sólo se oyen, lejos, voces.

Por las ramajes la luz rompe.

Tendida entre la yerba brilla verde.

[In the Deer Park Hermitage.

No people are seen on this mountain.

Only voices, far off, are heard.

Light breaks through the branches.

Spread among the grass it shines green.]

– Octavio Paz, 1974 (Paz, Versiones y Diversiones)

My superficial reaction after studying past iterations of “Lù Zhái” translations is that, across various spaces and times, despite most scholars starting from the same – if not nearly identical – crib, the room for interpretation is vast. Not only does the source language (SL) provide leeway in terms of translation, it also provides leeway in terms of understanding – ask two different Mandarin speakers to read the poem, and both will more likely than not interpret the piece differently. Part of this is due to Mandarin’s inherent linguistic superpositioning – that is to say, the fact that a singular character can hold various meanings – but another part is due to the nature of a poem. Poetry exists to be scrutinized, internalized, and interpreted in a way that is personal exclusively to the reader. It is both form-dependent and reader-dependent. Immediately, I knew that if I were to translate Wang Wei’s piece with any ounce of integrity, I needed to aim to preserve not only the poetic structure but also the feel of the piece, the imbued qualities that make it elevate beyond the level of mere prose.

An additional layer of complexity is that, depending on the target language (TL), or the language into which one is translating, the meaning and interpretive qualities of the piece can be further misconstrued or molded in ways both good and bad. Unlike Spanish or French, the first challenge I faced when translating into English was the issue of defining subjects and, unlike translating into Latin, defining specific articles. In the original Mandarin, there are no characters for ‘he/she’ or ‘a/an/the’ – the language is both context-dependent and innately modifiable by the written characters. In romance languages, we see this through verb conjugations. English has neither.

I came out of all of this knowing that, from a practical standpoint, I needed to (1) preserve poetic tonality and essence, (2) find a way to either create a plausible subject or adapt existing subjects to fit the piece, and (3) maintain poetic lyricism and rhythm by removing or modifying the presence of specific articles.

Once I had identified the pragmatic requirements, I was able to explore certain thematic qualities which I felt would be critical to my version. Though my final interpretive translation of Wang Wei’s “Lù Zhái” was looser than many of those presented in Weinberger’s 19 Ways of Looking At Wang Wei, I sought to recover what I thought many translators missed: the contextualization of Buddhism, natural spirituality, and cyclicality. Weinberger mentions translator James J. Y. Liu’s [3] use of the passive voice, a choice “made to feel the presence of Nature as a whole, in which the mountains, the human voices, the sunlight, the mosses, are all equals” (24). With this concept in mind, I further investigated the initial transliteration of “Lù Zhái” included at the beginning of Weinberger’s piece, which only included one definition for the Chinese character 空 (kōng) in its crib: “empty.” However, additional research yields approximations like “bare,” “hole,” “null,” and “in vain.” I followed the traditional Chinese roots of kōng further to examine whether or not the meaning changed in relation to Buddhism and discovered that the most frequent translation of kōng into English is ‘emptiness’ (Sundararajan), which is a very important concept in both Buddhist and Chinese Philosophy. In Buddhism all things are totally empty of any defining essence.

One of the standout aspects of Liu’s translation [3], as well as Paz’s [5], was the depiction of nature as something anthropomorphic, intelligible, and present. This resonated with my own initial interpretation of the emotive aspects of Wang Wei’s original piece, something connected to natural spirituality. Taking both this notion, as well as the Buddhist conceptualization of nature, ultimately led me to translate kōng as “senseless,” since I wanted to encapsulate the sense of purposelessness of the mountains as though they are almost defunct. From one perspective, it functions almost as a play-on-words in English, as “senseless,” preceded by the last syllable of “mountains,” retains a subconscious breath that forms when saying the two in combination, creating a muted “eh” sound. Coupled with “senseless,” I hoped that subconsciously this elision might trigger the notions of “essence-less” (i.e., lacking a fundamental essence). Moreover, it maintains the concept of “void” in a material reference to the lack of people. Another aspect I sought to preserve follows the historical mutation of the character wén, which in traditional Chinese meant ‘to hear’ while in the modern tongue more closely resembles ‘to smell.’ I translated it as ‘perceive’ to reflect a general awareness of sense (i.e., perception). Taking these ideas together, we get a unique play-on-words with “sense-less” that (I think) closely resembles the vivacity of nature, its ability to perceive, and draws parallels throughout the poem.

Moreover, I wanted to maintain Wei’s poeticism (albeit in my English translation). Since a true or direct play-on-words is near-impossible to translate, I interpreted other elements of the original Chinese into English by reimagining the closest sentiments present. As opposed to directly preserving them (i.e., translating directly), I opted to reimagine them through near-analogous English concepts and words. Among translation theorists, this is known as the ‘stylistic equivalency of expressive identity,’ something famously highlighted by Popovic, a linguist and translator. Weinberger includes a quote from Francois Cheng, who posits that the trope of “returning shadows” in the original Chinese signifies “rays of sunset.” I wanted to match this metaphor, but I also sought to complement it by highlighting the dynamic between voices, sound, and presence with emptiness, soundlessness, and absence. I thus translated xiang (‘to echo,’ ‘sound’) as ‘shadowed voices.’ In order to preserve the mysterious but playful nature of Nature itself, therefore, I attempted to juxtapose opposites to maintain the cyclicality of Nature (as with the sun rising and setting, the seasons, etc.): pairing “returning shadows” with “shadowed voices,” “senseless” with “perceive,” and “unseen” with “unseeing.”

I am reminded of the adage, “If a tree falls in a forest, but no one is around to hear it fall, does it make a sound?” Thus, I am left to wonder about the mountains: if there is nobody to witness their beauty, are they truly beautiful at all? In which case, are they senseless?

I also sought to encapsulate the flexibility and linguistic superpositioning of Chinese characters by translating bù jián (negative + ‘to see’) as simultaneously unseen and unseeing, which I intended to serve as a descriptor of the mountain and a personifier all the same. This further reinforces the potential for Nature to be mysterious – both two things at once and simultaneously neither.

Part of the benefit of translating from Chinese to another foreign language like French [2] or Spanish [5] is that personal subjects (“I,” “he,” etc.) are included in the conjugated endings of each word. Liu solved this by using the passive voice. I attempt to shift the focus by categorizing the mountain as an equal subject through the above personifiers. While these identifiers can be explicitly added (‘je’ or ‘yo’ meaning ‘I’, for example), each translation omits those, which further reinforces the sense of distance in the poem created by the mountains/hills (depending on what you interpret shān to mean). I chose ‘mountain’ because of the associations of grandness in size, but also the presence of chasms, valleys, and the physically imposing distance of such natural landscapes.

The choice of ‘breach’ as an equivalence to ‘ru’ intended to convey the fact that, much like a forest absent of witnesses, even the light itself might have difficulty entering through the forest. It conveys further personification of Nature (via light) by imbibing the act of passing through a shield of leaves as something requiring force, but also reinforcing the idea of Nature as shielded from the outside. It suggests that perhaps Nature is most beautiful when it is senseless, only able to be perceived by itself, in all capacities, and unable to be perceived by others. In other words, it suggests that perhaps Nature cannot be sensed at all, which emphasizes the mysterious allure of Nature and informs my choice to frame the first line as a question.

I chose to structure the first line of my translated poem as such because of the mysticism of Nature’s essence as portrayed by Wei and the multiplicities of Chinese characters. In my opinion, the unique ambiguity of this linguistic quality makes me, as a translator, think in terms of questions in which there can be more than one possible answer. This additionally reflects the adage I posed above, and also affronts the conflicting sense the reader perceives throughout the poem of the mountain’s purpose. By posing a question, it seems the poem itself is almost a search for meaning, value, or assurance; moreover, this forces a reader to think about the mountain’s seemingly conflicted meanings at the same time as the poem itself.

At last, we come to my final translation:

[6]

Are the mountains senseless?

Void of people, they are unseen, unseeing,

spare only to perceive shadowed voices.

Deep crepuscular light breaches the forest

Chasing away returning shadows beyond the jade grasses.

– Matthew J. Capone, 2023

Works Cited

Cestari, Matteo. “Between Emptiness and Absolute Nothingness. Reflections on Negation in Nishida and Buddhism.” Frontiers of Japanese Philosophy 7. Classical Japanese Philosophy 1 (2010): 320-346.

Choong, Mun-keat. The Notion of Emptiness in Early Buddhism. Motilal Banarsidass, 1999.

Fletcher, William John Bainbridge. Gems of Chinese Verse and More Gems of Chinese Poetry, 1919.

Law, Vanissa. Kong (2011). https://www.vanissalaw.com/kong-2011

Liu, James JY. The Art of Chinese poetry. University of Chicago Press, 1966.

Margouliès, Georges. Anthologie raisonnée de la littérature chinoise. Payot, 1948.

Paz, Octavio. Versiones y diversiones. J. Mortiz, 1974.

Sundararajan, Louise. “Toward a reflexive positive psychology: Insights from the Chinese Buddhist notion of emptiness.” Theory & Psychology 18.5 (2008): 655-674.

Watson, Burton. Chinese Lyricism: Shih Poetry from the Second to the Twelfth Century 115. New York: Columbia UP, 1971.

Weinberger, Eliot. Nineteen Ways of Looking at Wang Wei. New Directions Publishing, 2016.